GUY DEBORD'S GHOST

"Montaigne had his quotations; I have mine. Soldiers are marked by a past, not by a future. That is why their songs can touch us." Guy Debord. Panegyric: Volume 1

All my life I have seen only troubled times, extreme divisions in society, and immense destruction; l have taken part in these troubles. Such circumstances would doubtless suffice to prevent the most transparent of my acts or thoughts from ever being universally approved. But in addition, I do believe, several of them may have been misunderstood.

-Guy Debord, Panegyric

My method will be very simple. I will tell what I have loved; and, in this light, everything will become evident and make itself well enough understood."

-Guy Debord, Panegyric

Down from Luxembourg Gardens toward the Seine along St. Germain there's the Cafe des Flores and Sartre and de Beauvoir. Left and down from the Beaux-Arts de Paris, past L'Hotel where Oscar Wilde died from the wallpaper, before you reach the Seine and Booksellers of Paris, there's a dive called Chez Moineau. Wine costs 70 p per litre; hashish is plentiful.

There is no reality, no other realism, than the satisfaction of our desires."

-Guy Debord.

Here, in 1950, we meet Guy Debord, aged 19.

I headed first of all towards that very alluring milieu where an extreme nihilism no longer had any interest in knowing about or continuing any previously accepted way of life or use of the arts. This milieu readily recognised me as one of its own. Thus disappeared my last possibilities of one day returning to the normal round of existence.

Guy Debord. Panegyric: Volume 1.

A degree, even one from a University in Paris, would at best buy for a young man of his class and background a place in the civil service where advancement is sluggish, the wages meagre. If the alternative to the established, normal course of life was perdition, then perdition it will be.

He used his state allotment for tuition and upkeep to buy drinks for the other drop outs, deserters, Algerian refugees, delinquents, deviants, thieves, and outsiders barred from the straight world. They went to Chez Moineau to drink and vanish.

We know what this scene looks like because Ed van der Elsken was a habitué of Chez Moineau. The prodigiously talented Dutch photographer took pictures. His eye fell on Vali Myers, a wanderer and pagan, originally from Australia, but now at home in low dives in Paris. She becomes the centrepiece for van der Elsken's photographic novel "Love on the Left Bank." The photos show Vali dancing, loving, drinking, smoking hashish, discovering alternatives on the streets.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2011/feb/10/love-on-left-bank-in-pictures

Vali Myers will live into her seventies, and will die among friends and family in Australia. Here Robert Mapplethorpe photographs Patti Smith. If you notice the lightning bolt tattoo, it’s the one Vali gave her when they met at the Chelsea Hotel in 1973.

According the the Vali Myers Art Gallery Trust:

Vali’s first supporter in New York was Abbie Hoffman who introduced her to the Chelsea Hotel and its inhabitants. Andy Warhol suggested Vali print reproductions of her work to sell to enthusiasts. It was also at the Chelsea that Vali met a young Patti Smith. Vali’s war-paint had taken on permanence with intricate facial tattoos and Patti asked Vali to tattoo her knee with a tiny little lightning bolt in “tribute to Crazy Horse”.

Here Debord crosses into another world with its own history written by madmen, dreamers and criminals. This lineage, just counting the writers, stretches back to the criminal poet Villon, to Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud, to Isidore Ducasse (Debord took a certificate from the Isidore Ducasse Institute in Nice) who wrote, using the pseudonym Comte de Lautréament, a sinister novel "Maldoror" as well as poetry that Debord kept with him while writing the work for which he is known, “The Society of the Spectacle”.

The two world wars that the leaders of Europe's nations waged, to the their minds, for good reasons, left behind more victims than the dead on the fields of battle or in the camps. With the best intentions, the political leaders had murdered fellow feeling and decency, and if it ever really existed, innocence. Here in Paris you saw the victims, the traduced, the betrayed, the wounded, the mad, the predators, and those wised up to the inherent murderousness of their leaders and the cruel partiality of their laws and the prejudice with which those laws were applied.

For Debord, survival depended on a tight band of collaborators whose purpose is to live free of the dictates of this ruling order. Debord asserts that humans demand freedom to live according to their desires.

Paris in January of 1793: The revolutionaries invalidate the contract between the House of Bourbon and God with the stroke of a blade. Raising the severed head for the French people to see transformed them from subjects to citizens. They were now free.

Like that, things change. Starting in Paris, the Enlightenment dispensation of reason and authority started to crack and fall apart. The people marched. Royals put their money in offshore banks. Just in France, in the 19th century alone, Parisians took to the streets In 1830, 1848, 1870. In each case, they were defeated, killed and imprisoned by the police and soldiers of the State. But the precedent was established: feed the people enough shit, and they will rebel, notwithstanding the offer of a piece of cake.

Debord knew this history and more. He knew the path to freedom begins with the rejection of the ruling order. The times call for resistance. Debord heeds the call. But he's cunning, and keeps to the shadows, biding his time, preparing the field for battle. When someone called him an artist, he disagreed, “I’m a strategist”.

Debord starts his career as a provocateur and conceptual nihilist. He joined a brand new avant-garde movement, the Lettrists, self-proclaimed inheritors of Dada's mission to kill art. They started with language because it had been contaminated by its use in totalitarian propaganda. Their poetry they compose using letters not words. It becomes a primitive ur-language of noise and guttural sound. Their films string together nonsensical scenes with soundtracks of insults and noise. They become notorious for one of their provocations: during Mass in Notre Dame a Lettrist disguised in priest's vestments takes control of the pulpit and denounces God and the Church to the congregation. They go to jail; they have succeeded - they are now infamous.

Debord likewise tastes infamy when he shows his first film in 1952. "Howls for Sade" features a final 25 minutes of black screen. Its sound track is a symphony of sounds produced from both ends of the alimentary canal.

Audible anger grows during the screening. There follows a proper punch up. Debord quits the Lettrists, and sets up a splinter group, the Lettrist International. They don’t make art; they want to change the conceptual fabric of the world which has degenerated into violent, boring nonsense. They will start with their city, Paris. Their international cohort of subversives do the same in their cities, Copenhagen, Brussels, cities in Italy.

They follow specific practices that they invent: to reassert human imperatives in daily life, they remake the City into something new; they wander Paris, sometimes for days. These long walks without specific destination they call ‘dérives’, literally, ‘drifts’ but they are attentive to the 'forgotten desires' of the forgotten inhabitants of neighbourhoods spared destruction when Baron Haussmann’s wrecking crews ‘modernised’ Paris. They favoured the neglected parts of the city.

A character in Patrick Modiano’s novel about Debord, the Situationists, and Chez Moineau “In the Cafe of Lost Youth” calls these patches of undeveloped urban land or undistinguished blocks of mostly empty buildings “neutral zones”. Modiano’s novel centres this novel around characters who meet in a cafe. Its structure follows the lives radiating from that cafe in looping, ragged circles. Modiano’s novel is a series of interconnected dérives where characters find then lose each other. The feeling at the conclusion is one of a profound sense of loss, of lives lived in brief encounters.

Debord approached these walks with a sense of play. They often started at night when the bar closed and no one wanted to go home to their bedsits. So they wandered together, discovering the ghostly, emotional, hidden contours of their city, transforming Paris into a city of joy where they might bring their dreams to life.

Debord and his group also devised their own version of ‘situations’. Sartre a few streets over at his posh cafe theorised about ‘situations’. Sartre’s situations were conceptual nodes of thought, cognitive crossroads where one decides on a new direction. Debord saw 'situations' differently.

This perception is at the heart of all Debord's thinking and action. In 1952, when he was twenty years old, he called for an art that would create situations rather than reproduce already existing situations.

Five years later Debord's founding platform for a Situationist International (SI) contained a first definition of the spectacle: ‘The construction of situations begins beyond the modern collapse of the notion of spectacle. It is easy to see how closely the very principle of the spectacle, namely non-intervention, is bound to the alienation of the old world’ (Rapp., 699). The twelve issues of Internationale Situationniste (1958-69) attest to the increasing importance assumed by the notion of the spectacle in Situationist thinking. Its systematic analysis, however, awaited the appearance, in 1967, of the 221 theses that constitute Debord's The Society of the Spectacle.

Jappe, Anselm. Guy Debord (p. 6). PM Press.

But Debord’s most powerful weapon was his cutting wit and concise, acerbic prose. His writing appears first as polemics in publications by the Lettrist International and from 1957 until 1972 in publications by his new group, the Situationist International. The Situationists International resulted from a merger which saw the LI joining forces with other European avant gardes, and formidable artists like Asger Jorn.

His 1967 summa “The Society of the Spectacle” which we’ll examine in some detail, continues to exert influence with its prescient understanding that increasingly concentrated and unregulated capital formations have increasingly hollowed out our lives by draining them of anything but our numerical value in economic calculations which, as we saw in 2008, nobody understands.

Debord was a superb writer, but he saw his writing as a tool of thought, a weapon. He saw himself fighting his side with words.

Here’s an example where he expresses the importance of good writing to thinking, and conversely, how poor thought yields cliched language:

Those who wish to write quickly a piece about nothing that no one will read through even once, whether in a newspaper or a book, confidently extol the style of the spoken language, because they find it much easier, more modern and direct. They themselves do not know how to speak. Neither do their readers, the language actually spoken under modern conditions of life having been socially reduced to a mere representation of itself, as endorsed by the media, and comprising some six or eight constantly repeated turns of phrase and fewer than two hundred terms, most of them neologisms, with a turnover of a third of them every six months. All this favours a certain hasty solidarity. In contrast, I for my part am going to write without affectation or fatigue, as the most natural and easiest thing in the world, in the language I have learned and, in most circumstances, spoken. It's not up to me to change it. The Gypsies rightly contend that one is never obliged to speak the truth except in one's own language; in the enemy's language the lie must reign. Another advantage: by referring to the vast corpus of classic texts that have appeared in French throughout the five centuries before my birth, but especially in the last two, it will always be easy to properly translate me into any future idiom, even when French has become a dead language.

Art historian and theorist, and briefly Situationist, T.J.Clark writes about Debord's prose:

A great deal of the agony/comedy in Debord's prose is provided by the business of its continually swallowing, and half-regurgitating, monstrous Hegelian, un-French, unclear turns of phrase and thought - so that the reader is typically plunged, in a sentence or two, from icy Retz or La Rochefoucauld aphorisms, shining with hate-filled economy, on to smothering, fuzzy (inspiring) rigmarole, full of unrepentant dialectical tricks, like the best bits of Feuerbach or the young Marx.

Debord uses a technique specific to his writing and Situationist practice. Debord calls it ‘détournement’, which can be translated ‘plagiarism’. Debord in a process similar to sampling ‘borrows’ sentences from writers who influence his argument.

An example appears at the start of "The Society of the Spectacle". The first proposition in “Spectacle” reads, “In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.”

Debord’s first sentence mirrors the first sentence of"Capital" by Marx which reads, “The wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails presents itself as an immense accumulation of commodities.”

You see that Debord replaces Marx’s word “commodities" with his word “spectacles" in order to make the point that capitalism has evolved since Marx. The process of commodification, Debord argues, has accelerated and in effect commodified us in a process much more complex than the one Marx analysed. He calls this process the Spectacle. In this ‘détournement’ Debord ‘quotes’ Marx by putting his idea into play in the first of the 221 propositions that comprise the nine chapters of "The Society of the Spectacle, where he will expand Marx’s argument and refine it by détournements from George Lukács’ “History and the Origin of Class Consciousness” (1925), Hegel, as well as lesser known French writers whom Debord cherishes for their brevity and wit.

Here’s T.J.Clark again: he saw Debord’s compositional process at work when he visited Debord’s apartment:

The room on the rue Saint-Jacques where The Society of the Spectacle got written was at once an austere cell - with nothing on the shelves, I remember, but a few crucial texts (Hegel, Pascal, Marx, Lukacs, Lautreamont's Poesies) laid open at the relevant page - and the entryway to Debord's minuscule apartment, through which friends and comrades continually passed. The process was meant to be seen, and interrupted. One moment the deep, ventriloqual dialogue with History and Class Consciousness; the next the latest bubble for a comics detourne, or the best insult yet to Althusser and Godard.

Debord meant his writing to enter the world outside his room and create situations in order that people might feel free enough to change things.

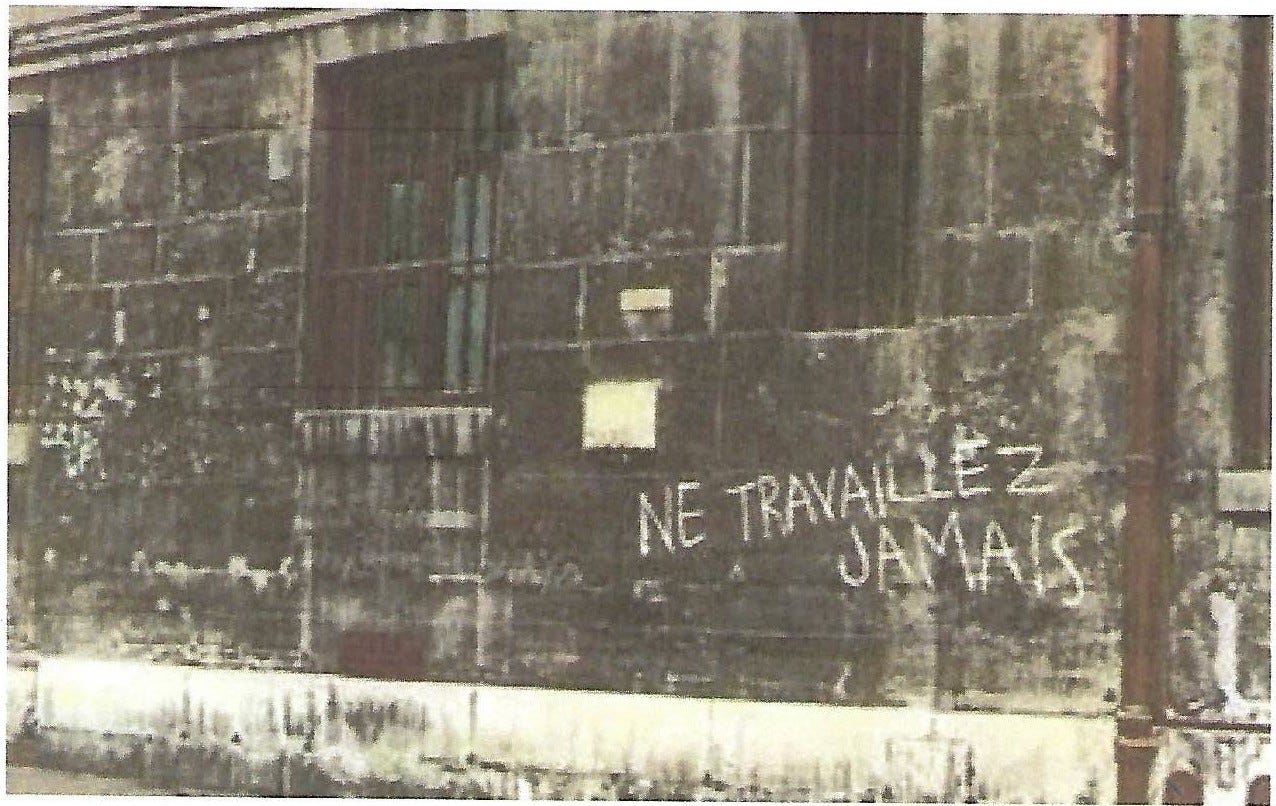

Here's a provocation Debord chalked on a wall near Chez Moineau -

It translates "Never Work". It first appeared when Debord chalked it on the wall in 1953 during one of his early dérives.

This graffiti appeared again in the months leading to May, 1968 when students and workers united in a protest that rocked the French Government of President Charles deGaulle and for a moment presaged another French Revolution. Debord and others claim he and the Situationists guided the thought and organisation of the demonstrators at the University of Nantere who went on strike, followed by the students striking at the Sorbonne in solidarity.

During that near-revolution in May, 1968, over a million French workers walked out of the Renault and other factories to join the striking students. This alliance of dissimilar and often hostile groups signalled to authorities a possible revolution.

Mavis Gallant reports from Paris, May, 1968

DeGaulle flew to an air base in West Germany, ostensibly to consult with one of his senior Air Force Generals. The order came for the police and French troops to use force: they moved in and ended the disturbance in the streets.

Debord, exhilarated as he may have been to receive credit for helping to foment the rebellion, was also anxious that the Security Services might assign him and the Situationists the blame, and take active measures to silence him.

Debord went underground, moving to Spain, Italy, and eventually settling in the rural fastness of Champot, in the Auvergne. It sounds remote enough to allow intensive reading and thought. He continued to write. “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle” appears in 1988, “Panegyric” in English in 1991. He describes the imperious nature, the harsh storms. It reminds me of the awe and deep renewal I feel in this remote corner of Cornwall where Katherine and I, and our rescue greyhound Florian, live.

But we do not play a table war game of my own invention called “Kriegspiel” as Debord and his wife and co-conspirator Alice Ho-Debord did. At least not yet.

It’s worth noting that Debord’s influence on the student revolutionaries derived from the ubiquity in 1968 of “The Society of the Spectacle”. It had appeared in 1967 and was avidly read. It suffices to note here that in the decade or so since the Spectacle first appears in Debord’s discourse, it had undergone refinement and gained explanatory breadth and depth in expression.

Its argument is still compelling.

Debord analyses a society ruled by money that through all governing institutions casts a spell over us by commodifying our work lives but also our leisure time, and by now, our private lives and bodies, enhanced since 1967 with invasive technology and surveillance.

Debord sees that we, as inhabitants in a real world governed by a sophisticated ruling order, have become consumers of images, commodified and subjugated by a system of wealth and power from which we benefit marginally, if at all. He called this system of control "the Spectacle". We exist in it, alienated, separate from each other, dejected and alone; but if we take steps to resist we might rediscover the freedom that is our birthright.

Debord was a great reader of Hegel. Hegel studied history to discover the process whereby it changes. So it was with wonder that Hegel considered that at one point human society tolerated ownership of other humans - slavery - in plain language. Hegel saw it as a milestone of human society’s progress that through an observable process, we changed our minds and ended slavery.

Change, then, is not an impossibility.

Debord wrote the work in despair, but the more I read, the more I see shafts of light. There’s the wit and the humour. He’s not dejected. He’s ready for the fight. And his actions and situations aim to exercise our comradeship and our imaginations so that we discover specific methods whereby we might break the spell cast by money that enthrals us, and to rediscover how good it is to live and play, to be human. Debord sought to restore in us the resolution to regain our freedom, our birthright.

I see the Situationists less as conceptual artists and more as a vanguard. A year of reading Debord and following all the tributaries he drew from and that flow from him has given me courage to think for myself and so yank myself from my despondency, which can be quite leaden and dull.

I see Debord’s actions and the situations he proposes as invitations to cast off the burden of the Spectacle to inhabit this world with pleasure, without the incentive to manipulate and exploit others. We don’t have anything but this world, and we only have one life, as far as we know, so why squander this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity?

I’m not alone. Others find Debord and the Situationists an inspiration. Greil Marcus writes about the dérives:

Guy Debord and a few other members of the Lettrist International group, known mostly to itself, which had split off from the Lettrists, a tiny, postwar neo-dada movement of anti-art intellectuals and students-devoted themselves to derives: to drifting through the city for days, weeks, even months at a time, looking for what they called the city's psycho-geography. They meant to find signs of what Lettrist Ivan Chtcheglov called "forgotten desires" - images of play, eccentricity, secret rebellion, creativity, and negation. That led them into the Paris catacombs, where they sometimes spent the night. They looked for images of refusal, or for images society had itself refused, hidden, suppressed, or "recuperated" images of refusal, nihilism, or freedom that society had taken back into itself, coopted or rehabilitated, isolated or discredited. Rooted in similar but intellectually (and physically) far more limited surrealist expeditions of the 1920s, the derives were a search, Guy Debord would write many years later, for the "supersession of art:' They were an attempt to fashion a new version of daily life - a new version of how people organised their wishes, pains, fears, hopes, ambitions, limits, social relationships, and identities, a process that ordinarily took place without consciousness.

Chtcheglov was in many ways the pioneer of these derives. This quote from his essay "Formulary for a New Urbanism":

SIR, I AM FROM ANOTHER COUNTRY

We are bored in the city, there is no more Temple of the Sun. Between the legs of passing women the Dadaists had hoped to find a monkey wrench, and the Surrealists, a crystal cup. That's gone. We know how to read faces [for] every promise - the latest stage of morphology. The poetry of billboards lasted twenty years. We are bored in the city, we have to push ourselves to the limit to discover still more mysteries on the street signage, the latest state of humour and poetry:

Patriarch's Public Baths Meat-cutting Machines Notre-Dame Zoo Sports Pharmacy

Martyrs' Convenience Store Translucent Concrete Golden-Hand Sawmill

Centre for Functional Recuperation Saint-Anne Ambulance

Cafe Fifth Avenue

Volunteers Street Extension Guesthouse in the Garden Hotel of Foreigners

Wild Street

And the swimming pool on the Street of Little Girls. And the police station on Rendezvous Street. The medico-surgical clinic and the free employment agency on the Quay of Goldsmiths. The artificial flowers on Sun Street. The Castle Cellars Hotel, the Ocean Bar and the Back & Forth Cafe. The Hotel of the Epoch.

And the strange statue of Dr. Philippe Pinet, benefactor of the insane, in the last evenings of summer. To explore Paris.

And you, forgotten, your memories ravaged by all the dismays of the world, run aground in the Red Cellars of Pali-Kao, without music and without geography, no longer on your way to the hacienda where the roots think of the child and where the wine ends in fables from an almanac. That's all over. You will not see the hacienda. It doesn't exist.

The hacienda must be built.

Yes, that Hacienda. And it was built, by Tony Wilson.’ Here’s his Hacienda as it was in Manchester.

(Image: Peter J Walsh/PYMCA/Avalon/Universal Images Group via Getty Images - via Manchester Evening News)

Or later,this:

(TateWard Auctions)

This image is Jamie Reid’s "detournement" used by the Sex Pistols and Malcolm McLaren, who read Debord, who considered himself a Situationist, who 'detourned' Situational thinking in the BowWowWow song”W.O.R.K”.

Punk makes sense as a Situation, read through Debord: it was a spontaneous action of sustained resistance against the ruling order (e.g.,"God Save the Queen", "Anarchy in the UK") in the spirit of revolution and play.

Viv Albertine tells how The Slits started: at the break in a guy-band gig, she and her band picked up the vacated instruments and started their band by playing their music over the hijacked sound system.

Pure Punk for Non-Plastic People.

More on the dérive as a cultural virus spreading the disease of free thought: Debord ransacked books for ideas to use as tools or weapons. He encountered an early version reading Thomas de Quincey, author in 1821 of 'The Confessions of an English Opium Eater:'

In the "Confessions" deQuincey recounts living when very young homeless on the streets of Soho. He made common cause with a young prostitute, Ann, 14, whom he met in the streets. They kept each other company, sleeping in doorways together for warmth and safety, sharing the food they scavenged. They fall in love, but one day, Ann goes missing.

Debord writes about de Quincy and Ann:

Psycho-geography is one of the aspects of the [conscious] arrangement of ambiance that one begins to call situationist...

The love story of Thomas de Quincey and poor Ann--who are fortuitously separated and seek in vain to find each other ‘in the immense labyrinth of London's streets, perhaps a few steps away’ -- marks the historical moment of the awakening to psycho-geographical influences upon the movements of human passion, and the importance of this moment can, in this regard, only be compared to the legend of Tristan, which dates the formation of the very concept of love-passion.

The hopeless condition of very large numbers of people-- experienced at the same time that the power of human society over nature had increased immensely-- appeared from then on in the culture of the innovators as an even-more acute contradiction between the affirmation of superior passionate possibilities and the reign of a certain kind of nihilism.

In Thomas de Quincey, these tendencies were tempered by the recourse to classical humanism, which the artists and poets of the century that followed would subject to an even more radical demolition. Nevertheless, we must recognise in Thomas de Quincey -- that is, when he wandered in London, always vaguely in search of Ann and looking at ‘several thousand female faces in the hope of seeing hers’: that is, between 1804 and 1812 -- an undeniable precursor to psycho-geographical derives: ‘On Saturday evenings, I have had the custom, after taking my opium, of wandering quite far, without worrying about the route or the distance (...) ambitiously searching for my Northwest Passage, so as to avoid doubling anew all the capes and promontories that I had encountered in my first trip, I suddenly enter a labyrinth of alleys, some of them terrae incognitae, and I doubt that they are marked on the modern maps of London.’

Debord, on his derives, like deQuincey, was looking for "a Northwest Passage", that mythical escape route to a paradise of satisfied desires, where the compulsions of money are lifted and we taste freedom.

A PERSONAL INTERVENTION

You can change your life. You cannot change its ending. Hollywood's business of happy endings is only the first of its deceptions. And the images presented on our screens are manufactured to extract from us every bit of value that can be totalled and banked.

In Hollywood, the sense of unreality is as relentless as the sun. The deceptions: eternal youth, wealth almost within reach, one's own importance, the pleasurable mastication by a cannibalism that consumes everyone.

There’s a lesser known film in the canon of Werner Herzog which I think about more and more often as I watch the movies and movie-making die - “Heart of Glass”.

The story is this: in a medieval German village everyone’s livelihood depends on the Glassmaker who possesses the secret to making a sublime ruby glass. But he dies without passing on the secret of making that ruby glass. So the rest of the movie observes the slow motion extinction of this town after its heart expires.

Herzog enhanced the slow motion by hypnotising the actors. I can’t say that it makes for a brisk evening of entertainment. But over the years I worked at the Studio, I watched money and the nomenklatura tasked with making sure us creatives didn’t muck up the business of making our movies day by day exert more influence. I watched more and more businesses - toys, music, theme parks, cruises, stock, and debt, and leverage - tarnish an ancient art. With every economy practiced, whatever business decision they made - e.g., make only blockbusters, make only superhero movies, make the same movie over and over - this nomenklatura lost sight of the secret of the ruby glass.

Now the only ones who remember are old and dying out. And if there’s one thing the villagers in Hollywood can agree, it is out with the old, and in with the...the same old thing. Over and over. Until the movie ends. Until there’s no more ruby glass, and the village and the villagers die. The nomenklatura will move on to cannibalise other businesses until they are cannibalised by machines. (For reference, see the “Matrix”. I had the pleasure of working on the early stages of the first movie. It almost didn’t get made: no one could figure it out. Now they can.)

I saw humanity beaten out of stories by sullen thugs who did not understand spirit or quality, and hated to the point of violence any suggestion they did not understand.

I left. They'll say they pushed me out before I jumped. They would. They're thugs.

My use value extracted I wandered. "I wandered lonely as a cloud.” Keats. A détournement.

No algorithm would have me. ‘Neither input nor output, he' - Polonius. Hamlet. A détournement.

My commodification complete, I disappeared.

I believe this feeling is called alienation.

Years and years of silence. Then grief. The thing about grief is it’s impossible to understand. Nothing else is understandable either. It kills explanations, excuses. No more happy endings. Just the ending. But when? And until then -

What’s next? The question a storyteller wants to hear.

Well, in my case, I saw a book. “The Society of the Spectacle”. Author? Guy Debord. I read some pages, I read some more. I kept reading, more and more. Sometimes it’s possible not to think about what’s next because the story right in front of you compels you to see the story hidden behind the words.

The book begins.

1

In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.

2

The images detached from every aspect of life merge into a common stream in which the unity of that life can no longer be recovered. Fragmented views of reality regroup themselves into a new unity as a separate pseudo-world that can only be looked at. The specialisation of images of the world has culminated in a world of autonomised images where even the deceivers are deceived. The spectacle is a concrete inversion of life, an autonomous movement of the nonliving.

I read this, and thought "The Walking Dead”. Why zombies? Why now? Because we’ve been turned into zombies by Corporations who took our souls. They turned us into zombies but the Corporation’s not done with us - we have become the Undead; our appetite is all that keeps us alive. We watch advertising, and it shows us what we want by showing us glimpses of the life we lost. We do what we’re meant to do: kill whatever stands between us and that morsel of the life we’ve lost and forgotten. That way each bite tastes new.

Or I change the channel. If I was still at the Studio I’d try to find some way to remake it.

I read on.

17

The first stage of the economy's domination of social life brought about an evident degradation of being into having - human fulfilment was no longer equated with what one was, but with what one possessed.

Welcome to Hollywood, Pilgrim.

24

The spectacle is the ruling order's nonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monologue of self praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life.The fetishistic appearance of pure objectivity in spectacular relations conceals their true character as relations between people and between classes: a second Nature, with its own inescapable laws, seems to dominate our environment. But the spectacle is not the inevitable consequence of some supposedly natural technological development. On the contrary, the society of the spectacle is a form that chooses its own technological content. If the spectacle, considered in the limited sense of the "mass media" that are its most glaring superficial manifestation, seems to be invading society in the form of a mere technical apparatus, it should be understood that this apparatus is in no way neutral and that it has been developed in accordance with the spectacle's internal dynamics. If the social needs of the age in which such technologies are developed can be met only through their mediation, if the administration of this society and all contact between people has become totally dependent on these means of instantaneous communication, it is because this "communication" is essentially unilateral. The concentration on these media thus amounts to concentrating in the hands of the administrators of the existing system the means that enable them to carry on this particular form of administration. The social separation reflected in the spectacle is inseparable from the modern State - that product of the social division of labor that is both the chief instrument of class rule and the concentrated expression of all social divisions.

Two things: 1) Debord didn’t know about cell phones or the internet, yet he’s forensically analysing what it’s like to live on networks centred in a phone in our hand that’s reporting everything about us to a technology that surveils us for data it can sell, without us ever seeing a penny or a pence. So there’s that;

2) T J Clark said that Debord ‘ventriloquised’ other writers. We read Debord in the Proposition 1 of the “Spectacle” ‘détourn’ or ‘sample’ Marx’s “Capital”. Here Debord’s doing the same thing with George Lukács, who writes about this fabricated economy of things and our role in it as a ‘second nature’.

Nature is something else. You need a tool to sew, you make a needle. Second nature begins when you need to work at a needle factory making more needles than you can ever use, but that will be sold for a tidy profit, you get your wage packet, and on the weekend you go shopping for something shiny and new that promises pleasure.

That process involves ‘commodificaton’ or selling things not for use but for profit. If you have money to spend and can afford it, you look for the ‘brand’ that connotes luxury and status, then you are responding to the commodity as to a ‘fetish’ - you pay extra for the juju or magic that the brand adds, even if the jeans were made in the same factory in the Philippines as the jeans selling on Amazon under their Essentials brand.

You go to work, you get your pay, you buy something shiny. The boss counts the cost of paying you and frowns. Then the boss counts all the money made from all the needles you and all your co-workers made that sold for a considerable profit, and the boss smiles. The amount of your wages fills the spot where a variable waited to be assigned a number. With your number assigned, the equation is calculated.

You’ve been reified, my friend. And your apartment that you can’t afford, your rent that you can’t pay, would go to a property management firm operating on behalf of a hedge fund investing, among other things, in urban residential real estate, and they’re using money being laundered by a shell company in the Bahamas to game their linkage in the System. At least you don’t have to worry about the money you lost on crypto because you’re too broke to play that game. Maybe a lottery ticket on the way home, and a takeaway curry.

In fact, none of this feels like a game. In fact, it all feels too much like work, which is exactly what it is, work. The beneficiaries of the confidence game live in the Bahamas or other tax havens.

That is alienation, my friend. It comes from being reified. We are no longer human, exactly. We inhabit a ‘second nature’ of man-made things (in this case may I be excused the gendered language?)

All of this I’ve only partially learned and somewhat digested in the year since my first reading of “Spectacle”. It turns out that my mind atrophied in the Corporation. But then as I read more, and specifically to pin down what exact phenomenon Debord described using what feels very much like an elusive and shifty metaphor, I began to find points of focus, particularly in the commentary on the ideas Debord used his image - the Spectacle - to dramatise. Reification is one of these concepts, and it is revelatory. Lukács coined the term 1925; it is itself a ‘reification’ of a confluence of ideas from Marx, Hegel, Novalis, Hôlderlin, and his teachers Max Weber and Georg Simmel.

It’s basically this, in the process of commercialising everything, we too have been commercialised.

I experienced this in Los Angeles, in Hollywood where I discovered I had 'friends’ when I could do something for them. When I could no longer do things for my ‘friends’, then they were no longer 'friends'. They don’t respond to phone calls or emails. And why should they? They are searching for other people whose commodity value they might exploit.

It turns out that George Lukács noticed something similar in Weimar Germany. He analysed people’s behaviour and needed to find a word to describe what he observed.

Axel Honneth in his 2005 Tanner Lecture on "Reification" describes what Lukacs saw and what it led him to think:

In the German-speaking world of the 1920s and 1930s, the concept of ‘reification’ constituted a leitmotiv of social and cultural critique. As if refracted through a concave mirror, the historical experiences of rising unemployment and economic crises that gave the Weimar Republic its distinctive character seemed to find concentrated expression in this concept and its related notions.

Social relationships increasingly reflected a climate of cold, calculating purposefulness; artisans' loving care for their creations appeared to have given way to an attitude of mere instrumental command; and even the subject's innermost experiences seemed to be infused with the icy breath of calculating compliance. An intellectually committed philosopher's presence of mind was needed, however, before such diffuse moods could be distilled into the concept of "reification:' It was Georg Lukacs who, by boldly combining motifs from the works of Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel, succeeded in coining this key concept in a collection of essays published in 1925 and entitled History and Class Consciousness. In the centre of this volume so fuelled by the hope of an impending revolution is a three-part treatise on ‘Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat’.

Mitchell Cohen in the Los Angeles Review of Books reviews the centenary edition of "History and Class Consciousness" and identifies the revolutionary potential inherent in the idea of 'reification' - if only its victims understood their victimhood and would take action.

Simmel's The Philosophy of Money(1900) proposed that societies dominated in all their facets by monetary exchange wind up dissolving life's most compelling questions; quantitative issues displace qualitative ones. Weber proposed that the whole of modern society had been ‘rationalized’ by capitalism, making everything calculable and computable. Yet what happens, he wondered pointedly, when matters of value, indeed the entire world of human values, becomes no more than mere calculation?

Reification thwarts recognition of human agency, as ‘things’ on markets seem to constitute an unchangeable ‘second nature’. Recognition by the proletariat that another arrangement is possible - a coming to consciousness of the humanity that lies obscured within commodities - must therefore threaten established order.

Debord concludes the First Chapter of "The Society of Spectacle" with this dirge on the theme of alienation:

30

The alienation of the spectator, which reinforces the contemplated objects that result from his own unconscious activity, works like this: the more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he identifies with the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own life and his own desires. The spectacle's estrangement from the acting subject is expressed by the fact that the individual's gestures are no longer his own; they are the gestures of someone else who represents them to him. The spectator does not feel at home anywhere, because the spectacle is everywhere.

George Lukács attended Max Weber’s lectures and studied Weber’s analysis of society and its “disenchantment”. Weber writes, “The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world.” Reason and its science had indeed demystified the world, banished gods, scrubbed modern existence clean of any clinging mystery, leaving us with what, exactly? Disenchantment. Depression. World War.

Sound familiar? Debord never out and out says so, nor does he name names, but here marks a point where economies of many nations acting together with their State franchise may have found survival of the capitalist system less possible through reform than through re-mystification of the economy. In this there are always serviceable fictions to weave into the triumphal narrative of Capital - trickle-down, supply side, crypto, deregulation, banks financing risk (especially if the State will cover the risk), distressed assets.

Philosopher Raymond Geuss does a good imitation of trickle-down advocacy in the context of putting it in the context of the value philosophy of John Rawls:

Crudely speaking, this theory eventually takes this form: ‘Value’ is overwhelmingly produced by especially gifted individuals, and the creation of such value benefits society as a whole. Those who are now rich are well-off because they have contributed to the creation of ‘value’ in the past. For the well-off to continue to benefit society, however, they need to be motivated, to be given an incentive. Full egalitarianism will destroy the necessary incentive structure and thus close the taps from which prosperity flows. So inequality can actually be in the interest of the poor because only if the rich are differentially better-off than others will they create value at all—some of which will then “trickle down” or be redistributed to the less well-off. Rawls allows people who observe great inequality in their societies to continue to feel good about themselves, provided that they support some cosmetic forms of redistribution of the crumbs that fall from the tables of the rich and powerful. The apparent gap which many people think exists between the views of Rawls and, say, Ayn Rand is less important than the deep similarity in their basic views.

The people, to the degree that they pay any attention at all, prefer a narrative that sounds good, to the facts which are intractable, messy, complicated. About 43.9 percent of participating Germans cast their ballot for Hitler in the last free German election. Trump polls on either side of that number but hovers about where Hitler polled during the last election before the Reichstag fire and his assumption of Executive Powers.

The point seems to be that a significant proportion of the people in most capitalist countries are willing to support policies that curtail their freedom provided they are protected, and how they are protected is less important than that they feel so. Is freedom too fraught with uncertainty? Better if you think the world is too uncertain, that a strong person put you to sleep with a good narrative.

And what better medium to convey those narratives than television. In the Sixties when asked when the Spectacle was ‘invented’, Debord said it began to consolidate ‘about forty years ago.’ John McCrary does the math and points to the invention of television in 1927 as a possible catalyst to the Spectacularisation of the commodity economy. The first cell phone was made in 1973. In 1979, Nippon Telephone and Telegraph launched the first cell phone network. The UK got its first network in 1985, two years after the US. Google started in 1998. I was ‘browsing’ the internet before that when Google was one search option, alongside Ask Jeeves.

If the medium is the message, the message relies on the medium to tell its story. It is a fact that what Debord calls the Spectacle rises in chronological time alongside networked communication and the proliferation of broadcast images and advertising. But Debord distinguishes the Spectacle from the media of his day: his point, simply, is that the Spectacle, like Soylent Green, is people. We put it in place. The hopeful note in Debord, counterpointing his dirge of despair about our present ensorcellment, is that we put this damn thing in place, we can disconnect it.

In the summer of 2022, I stopped posting on Facebook and Twitter. I post this essay on Substack and when I publish it I let Substack push it through Facebook and Twitter. I feel better, I must say.

32

The spectacle's social function is the concrete manufacture of alienation.

34

The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point that it becomes images.

Even so, more than a year later, I can’t give you an exact answer to the question, ‘what is the Spectacle?’ I just know I live inside it. I’m not being glib. I believe Debord meant ‘the Spectacle’ to function like a figure in literature, a flexible and suggestive term that applies differently in many instances. When I read Debord and see how many screens people disappear into even crossing the street in London traffic, I believe he had the powers of a seer.

T. J. Clark's attempts an explanation of the Spectacle in his Introduction to "Painting in the Modern World" before turning to the last chapter of “The Society of the Spectacle”.

It’s worth noting that he’s defining the term to use in his study of modern painting because the Spectacle, even in its elusive metaphoric state, nonetheless describes real processes in the real world that we feel impinging with very real and oppressive force.

About the concepts of the 'spectacle' and 'spectacular society' it is not so easy to be cut and dried. They were developed first in the mid-1960's as part of the theoretical work of a group called the Situationist International, and they represent an effort to theorise the implications for capitalist society of the progressive shift within production towards the provision of consumer goods and services, and accompanying 'colonisation of everyday life.'...

It points to a massive internal extension of the capitalist market - the invasion and restructuring of whole areas of free time, private life, leisure, and personal expression

…

It indicates a new phase of commodity production, the marketing, the making-into-commodities, of whole areas of social practice which had once been referred to casually as everyday life.

The concept of spectacle is thus an attempt - a partial and unfinished one - to bring into theoretical order a diverse set of symptoms, ‘consumerism', for instance, or 'the society of leisure'; the rise of mass media, the expansion of advertising, the hypertrophy of official diversions....

The Situationists were primarily interested...in the possible or actual crisis of this attempt to regulate or supplant the sphere of the personal, private, and everyday.

They put great stress on, and a degree of faith in the signs of strain in just this area: the question of Youth, the multiplication of delinquent subcultures, the strange career of 'clinical depression', the inner city landscape of racism and decay.

One other feature worth noting is the contentious nature of the Spectacle, wherein the schismatic anger on the left on issues of language and definitions excites more passion than a spirited, strategic defence of a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body without state coercion. With these distortions of language come distortions of thought.

The Spectacle becomes a nightmare that devises an escape room where players competing by using perceptions to make clashing judgements formed of opinions that may or may not be true. The nightmare consists of never finding the way to escape this room. It’s a game of high pointlessness, but when its value as a distraction diminishes you feel acutely the truth that you are its prisoner.

The Spectacle, in my mind, bears a striking resemblance to the Cave Plato imagined for his parable in Book VII of his “Republic”. There inmates chained to a wall argue about the identity and nature of shadows cast on the wall in front of them. Chained facing front, they cannot turn to see that puppets cast the shadows that they imagine to be real things in the world. This shadow theatre is all these prisoners know of reality. For some people, this is enough. I have seen enchainment defended because it favours a studied competence with opinions in which we must traffic everyday. I confess I do not share this view. It’s a claustrophobic and frightening scenario, and even thinking about it I want sunlight and fresh air.

Raymond Geuss I turn to again, in part because I like his writing, but also because the prison analogy gets at the feeling of being deceived or being subject to authority. It’s just something I’ve always hated, to an irrational degree perhaps, but the Spectacle is another one of the infernal machines devised, like prisons, to contain us. And I don’t like prisons, even as a visitor, or as a reader of analogies:

A prison warden may put on a benevolent smile (Rawls) or a grim scowl (Ayn Rand), but that is a mere result of temperament, mood, calculation and the demands of the immediate situation: the fact remains that he is the warden of the prison, and, more importantly, that the prison is a prison. To shift attention from the reality of the prison to the morality, the ideals and the beliefs of the warden is an archetypical instance of an ideological effect. The same holds not just for wardens, but for bankers, politicians, voters, investors, bureaucrats, factory workers, consumers, advisers, social workers, even the unemployed—and, of course, for academics.

Buried somewhere in here is the fact that the prison door locking us into the prison of the Spectacle closes without much protest from the inmates. It’s not guaranteed, should the door open in our lifetime, that we would want to leave our phones behind. But Debord is making the point that it is our choice. We could become human again, with all the uncertainty and loneliness that entails. Having experienced a bit of it in my post-Spectacular life in Cornwall, estranged from Hollywood, I prefer it to alienation or Netflix.

Geuss mentions ideology, and how its identifying mark may work like a fingerprint, it can only individualise us, mark us as who we are, whether we want it to or not. Sometimes, I imagine living without ideological identifying marks so that I can travel more places and avoid fights. But some fights are worth having. It may be in the nature of a democracy to have fights, and it’s the ideology of autocracies with its militias and moral police, and the enforced stupidity of party lines that might rouse me to fight.

I mention ideology because it’s the subject Debord chooses to finish “The Society of the Spectacle” in ninth and last chapter.

Chapter 9: Ideology Materialized '

Self-consciousness exists in itself and for itself only insofar as it exists in and for another self consciousness; that is, it exists only by being recognised:'

-Hegel,The Phenomenology of Spirit

212

Ideology is the intellectual basis of class societies within the conflictual course of history. Ideological expressions have never been pure fictions; they represent a distorted consciousness of realities, and as such they have been real factors that have in turn produced real distorting effects. This interconnection is intensified with the advent of the spectacle - the materialisation of ideology brought about by the concrete success of an autonomised system of economic production - which virtually identifies social reality with an ideology that has re-molded all reality in its own image.

215

The spectacle is the epitome of ideology because in its plenitude it exposes and manifests the essence of all ideological systems: the impoverishment, enslavement and negation of real life. The spectacle is the material expression of the separation and estrangement between man and man. The ‘new power of deception’ concentrated in it is based on the production system in which ‘as the quantity of objects increases, so does the realm of alien powers to which man is subjected’. This is the supreme stage of an expansion that has turned need against life. 'The need for money is thus the true need produced by the modern economic system, and it is the only need which the latter produces’ (Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts). Hegel's characterisation of money as ‘the life of what is dead, moving within itself’ (Jenenser Realphilosophie) has now been extended by the spectacle to all social life.

217

...Society has become what ideology already was. The fracturing of practice and the anti-dialectical false consciousness that results from that fracturing are imposed at every moment of everyday life subjected to the spectacle - a subjection that systematically destroys the ‘faculty of encounter’ and replaces it with a social hallucination: a false consciousness of encounter, an ‘illusion of encounter’. In a society where no one can any longer be recognised by others, each individual becomes incapable of recognising his own reality. Ideology is at home; separation has built its own world.

Ideology evokes two opposed responses: I hate it because it’s often the tool of oppressors to make us knuckle down and obey, as the State does in China through its ideologically-driven Party governance. But I see how it also may become a tool of liberation when it results in manifestos, like this essay aims to be, or a real one, like Charter 77, which helped liberate Czechoslovakia, or Tom Paine’s “Common Sense” which pointed colonists toward declaring independence of their colonial masters in Britain.

“The Society of the Spectacle” I read as a Manifesto. It also bears the marks of a political document written by a man aware of being under police watch in a hostile state. It’s cagey. The Spectacle functions, as I’ve noticed, symbolically, evading direct testimony that could be used against you in a state trial. Perhaps it’s useful to notice that Christ also shrouded what he had to say in parable. So, too, we use irony - ‘the language of slaves’ - to mask our intended meanings. LOL.

We all feel under surveillance, because we are. We all feel we could attract the unwanted attention of the moral police, not because we are women who bare our heads in Iran, but because there are ideologists whose principal amusement, like members of the Puritan communities in New England, or the informants in Occupied Paris or Soviet Moscow, or ardent proclaimers of the Progressive Left or enraged school boards in Florida, consists in finding victims to pillory and then handing out vegetables to toss. Anyone could become a Jacobin and raise a fresh head for the admiration of their specific crowd. It’s a good way to add likes, add views, make new online friends, burnish your brand; who knows you may even get their job.

Debord was not a communist in part because he knew about the show trials and the gulags. But then he is not a capitalist because I suppose he was not the sort of guy to walk by someone suffering and leave them to die in the street.

In 1994 when his money ran out, he signed his future rights and royalties to his wife Alice. They ate well and drank good wine. As the evening deepened on 30th November 1994 in Champot, in his favourite chair, his reading chair, Debord chose the time of day when he came into the world in 1931 to leave it.

Yesterday marked the 29th anniversary of Debord’s death. I wrote earlier that I started reading him when harrowed by grief. Words would not come. Past events in sum amounted to nothing. My career by then was finished. I will probably not get another job. My age is part of it. As it should be clear by now, I’m also a refusenik.

Staring through my large front window at old trees and the magpies and crows that make them way stations on their long journeys became a reliable occupation. I read a book about British Surrealists because it was there. It mentioned the Lettrists and Debord. Curiosity was the first system to return to service after my great storm. I started this Substack, and took BareRuinedChoir from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 where the words sound the melancholy tone of the wind through a ruin.

I began to piece together my life, and what it meant. ‘Ruins’ became a useful metaphor. So did an adjacent metaphor, ‘archaeology’. Delving into the chaos of events led to discoveries of pieces of my life I’d discarded or forgotten. For example, I started out as a writer. I put that aside to take a job in the studio because I was scared of going broke. I’m still scared of going broke, but it struck me that all the time I spent not writing, but making a living in the ’second nature’ that Studio economies provided, had not removed this gnawing anxiety.

Reading “The Society of the Spectacle” enabled me to see the pieces of my life didn’t hold together because it was a simulation of a life formed from an all encompassing structure of of fabricated images - The Spectacle. My life fell to pieces because real grief exposed the flimsiness of the structure.

Reading more I learned that I lived in a ‘second nature’, the Matrix, if you will. Reading Debord ‘sampling’ Lukács, I learned about ‘reification’ - the process whereby everything and everybody we see, including ourselves, are commercialised.

To mortgage the house and lease the car, I contracted myself to the Studio and helped make their movies. But as meaning deserted the movies commodified within the Spectacle, so it departed me. I remember rising early one winter to make an hour free each morning to read “Man without Qualities” by Robert Musil. I wanted to leave then, but by then there’s a mortgage and a lease, and something Debord helped me put a name to - alienation.

So it was helpful to read Debord to demystify my alienation and show, along with Lukács, that in this ‘second nature’ of transactions emptied of meaning I developed ‘false consciousness’ which enabled me to continue contributing what value I had to the Spectacle. Funny enough, I noticed that the characters in the movies we made featured characters who, when you exclude their universe-wide motive for revenge, are all just cut outs, voids who move where the plot requires as the machinery of the Studio machine dictates more ‘content’. The Man without Qualities makes movies without quality.

In the Spectacle, no one can hear you scream.

But reading Debord lifted the mask. I caught a glimpse of what’s behind this ‘false consciousness’. What did I see? Something like real life, which at this point, I remembered: an open space where we’re free to think and talk, and imagine a better life and how to make it.

Reading more led me to discover that change, if you read history, does occur, when people have the sagacity and courage to make it happen. Hegel’s insight surprised me with its simplicity. Society accepted slavery, then ended slavery. Why? Because the belief became a fire in the mind that our essential nature requires freedom. So too, monarchs rule by divine right, until people revoke that right. Change, in other words, is not impossible but requires that people use their freedom to change things.

I learned from this instance the value of studying history: it gives us plentiful examples of people demonstrating the courage and sagacity to claim their freedom. That rang a bell: a hard, fast rule laid down in the entertainment industry by executives in the UK and US is that we do not want stories set in the past. No history, in other words, just a permanent now.

It’s poor form to expose contradictions in their thinking by mentioning movies like “Titanic” or “Gladiator” or shows like “Bridgerton”. But why this severe allergic reaction? I can’t make sense of why they would say something that they must know is contradictory - I know they’re busy and barely have time to think - but I suspect it has something to do with the power, as I read, that history has to show the course of events and how people do sometimes change them.

Debord makes it clear why. The Spectacle wants the same story over and over, the same hamburger, the same toothpaste, varied with different colours and flavours, but the same happy meal over and over. The longer we’re happy, the longer we can forego the messy business of change. The alternative version sees a world in which we have original ideas and imagine ways things might be otherwise. They once made movies like these; they could do so again. I was alive and witnessed original ideas being made: a first script, The Matrix, a manuscript by a first-time Scottish writer about a boy wizard Harry Potter. Originality is only unprofitable if people are unwilling to take the chance to profit from it.

But them’s the facts, and the facts are stubborn things. My favourite movies show people rising to fight injustice and change the world. Reading Debord put my life back in my hands. Rather than a ’second nature’, I have a ‘second chance’.

RIP, Guy Debord