MONTAIGNE: "Thus, reader, I am myself the matter of my book..."

"Had I been placed among those nations which are said to live still in the sweet freedom of nature's first laws, I assure you I should very gladly have portrayed myself here entire and wholly naked."

Substack by its nature encourages our writing to adopt the essay form. Over the four and a half centuries since Montaigne gave these prose explorations the name essay, or ‘essai’ in his French, we’ve used its flexibility to explore the world and our selves. Along the way, thinking has come more and more to depend on the creative exercise of choice and judgement, taste and style, intelligence and wit, that the essay allows.

When I write essays, I thank Montaigne. I often return to his essays for instruction and inspiration. His tone is that of a reasonable person who tries to understand what he does not understand. He reads; he listens; he observes. He follows his curiosity, but studies a subject from more than one angle, and this scrupulousness embodies his honesty. His wit often derives from his frank admission of subjectivity and the limits of his knowledge. He does not overstep this careful practice into rant or hyperbole.

Received wisdom has it that Montaigne ‘invented’ the essay. He is the first writer to call his writing in this new form an ‘essay’ or ‘essai’. The French word derives in part from the verb ‘assayer’, to weigh, to decide value. It’s a word better known in the weight and valuation of metals and materials.

The business world of the ‘Assay’ provides another word, ‘scruple,’ that is used as a metaphor for assiduous pursuit of accuracy. It’s that little bit of weight that the Assay uses to balance the scale to establish the exact weight and value of the object under consideration. A ‘scruple’ is also the niggling pebble in your shoe which drives you nuts until you shake free of it. It’s what makes Columbo turn around to ask one last question.

‘Essai’ also connotes ‘attempt’ or ‘work’. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) kens other meanings for ‘Essai’ as it might be translated to serve as the title of an English edition of Montaigne’s essays:

To translate the title of his book as “Attempts” would capture the epistemic modesty of Montaigne’s essays, while to translate it as “Tests” would reflect the fact that he takes himself to be testing his judgment. “Exercises” would communicate the sense in which essaying is a way of working on oneself, while “Experiments” would convey the exploratory spirit of the book.

As for the claim that Montaigne invented the form, the writer in the IEP corrects that assertion by pointing out Montaigne’s classical Roman antecedents:

…Plutarch, for example, Montaigne’s favorite writer and philosopher, could be said to have written such “essays,” as could Seneca, another ancient author from whom Montaigne borrows liberally. Second, Montaigne, who referred to the individual units of his book as “chapters,” never published any of those chapters independently.

Gore Vidal writes feelingly in his review of two translations of Montaigne’s Essays, one by Donald M. Frame, the other by M. A. Screech. The review can be found in Vidal’s “Collected Essays”. Vidal started his reading of Montaigne with Montaigne’s Essay “On Lying”:

Montaigne naturally hated lying, and it was his essay on the subject that first drew me to him years ago. ‘Lying is an accursed vice. It is only our words which bind us together and make us human. If we realized the horror and weight of lying, we would see that it is more worthy of the stake than other crimes…. Once let the tongue acquire the habit of lying and it is astonishing how impossible it is to make it give it up’ (I 8). As one who has been obliged to spend a lifetime in diverse liar-worlds (worlds where the liar is often most honored when he is known to be lying and getting away with it), I find Montaigne consoling.

Vidal, Gore. The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal (Vintage International) (pp. 224-225). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Vidal supposes what exigencies and influences may have induced Montaigne to write in this particular form. In 1571, Montaigne retired “long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employment…” to Montaigne, his family domain, to his chateaux, and his vast personal library…

…where he then began to make attempts at understanding everything, which meant, principally, the unknowable (so Socrates thought) self. In the absence of a friend to talk to or an Atticus to write to, Montaigne started writing to himself about himself and about what he had been reading which became himself. He made many attempts to try—essayer—to find his form. ‘If I had somebody to write to I would readily have chosen it as the means of publishing my chatter…. Unless I deceive myself my achievement then would have been greater’ (I 40). At first, he wrote short memoranda—how to invest a city, or what one is to make of a certain line of Seneca. Later, he settled for the long essay that could be read in an hour. He did a lot of free-associating, as “all subjects are linked to each other” (III 5).

Vidal, Gore. The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal (Vintage International) (pp. 225-226). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The origin of Montaigne’s writing seems to have been his curiosity and avidity for inquiry and understanding. Also, his reading. Understanding entails reading; reading entails writing; writing leads to understanding.

Vidal says that the King of France traveled to Montaigne to make him a counselor at his court “had the essayist not made one final attempt to understand death—life by dying.”

Vidal offers this epitaph:

The greatest action of this man of action was to withdraw to his library in order to read and think and write notes to himself that eventually became books for the world:

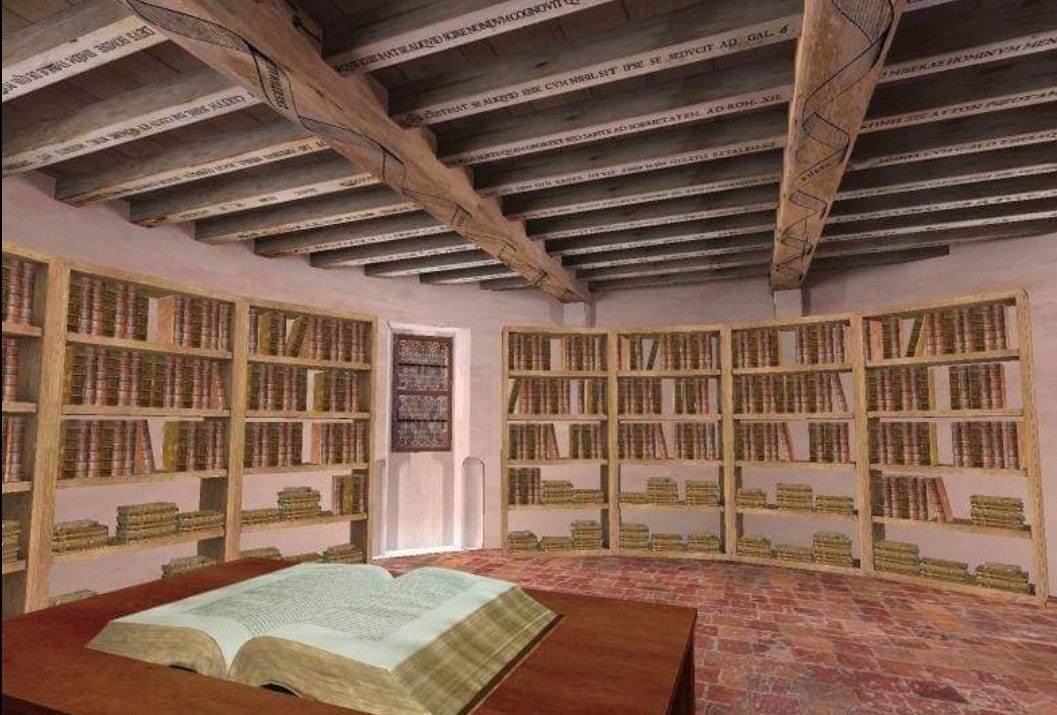

‘At home I slip off to my library (it is on the third storey of a tower); it is easy for me to oversee my household from there. I am above my gateway and have a view of my garden, my chicken-run, my backyard and most parts of my house. There I can turn over the leaves of this book or that, a bit at a time without order or design. Sometimes my mind wanders off, at others I walk to and fro, noting down and dictating these whims of mine…. My library is round in shape, squared off only for the needs of my table and chair: as it curves round, it offers me at a glance every one of my books ranged on five shelves all the way along. It has three splendid and unhampered views and a circle of free space sixteen yards in diameter’ (III 3).

Vidal, Gore. The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal (Vintage International) (p. 226). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Montaigne’s Library

Note his tone: Montaigne sounds like us. His magpie habits appear luxurious to those of his readers who still have to work, but to those of us retired or exiled from the world of court and commerce, it’s hard not to see that the essay, as Montaigne embarked on his essais, has its origins in the full voluptuousness of the book, the library, the archive, and the uncoerced and fluid drift of that malleable element that flows through all of our lives, Time.

I do something very similar. Not in imitation, but because as many of you know, there’s no better way to find what we must write in order to understand anything we might encounter on our path through this world that might stir our curiosity than to read and wonder.

Here we read for starters, Montaigne’s preface to his Essais:

MONTAIGNE PREFACE TO ‘ESSAIS’

This book was written in good faith, reader. It warns you from the outset that in it I have set myself no goal but a domestic and private one. I have had no thought of serving either you or my own glory.

My powers are inadequate for such a purpose. I have dedicated it to the private convenience of my relatives and friends, so that when they have lost me (as soon they must), they may recover here some features of my habits and temperament, and by this means keep the knowledge they have had of me more complete and alive.

If I had written to seek the world's favor, I should have bedecked myself better, and should present myself in a studied posture. I want to be seen here in my simple, natural, ordinary fashion, without straining or artifice; for it is myself that I portray. My defects will here be read to the life, and also my natural form, as far as respect for the public has allowed. Had I been placed among those nations which are said to live still in the sweet freedom of nature's first laws, I assure you I should very gladly have portrayed myself here entire and wholly naked.

Thus, reader, I am myself the matter of my book; you would be unreasonable to spend your leisure on so frivolous and vain a subject.

So farewell. Montaigne, this first day of March, fifteen hundred and eighty.